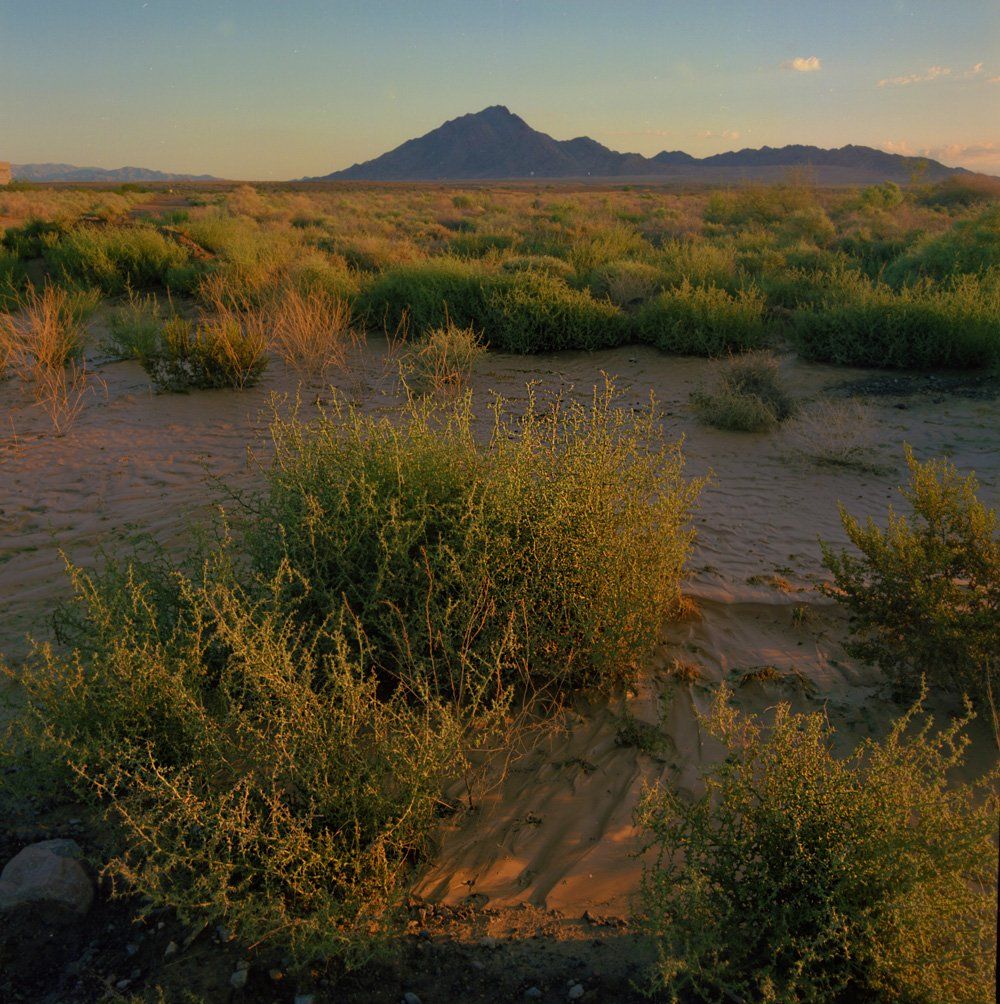

It was in these bottomlands of the Las Vegas valley that I developed an appreciation for the value of the most ordinary, and often ignored and abused landscapes. While a high school student the Las Vegas Wash became my Walden, a place described by Thoreau in words that mirror the Wash, a landscape which “does not approach grandeur, nor can it much concern one who has not long frequented it or lived by it.” While a high school student, I photographed avocets and eagles; made a 30-minute 16mm film, and wrote several pieces for the local Las Vegas newspapers. This work garnered enough attention that when I graduated, I was offered a job as a wildlife photographer in the Everglades for the Florida Fresh Water Fish & Game Commission. So, I left one swamp for another. During the intervening years after high school and my next visits to the Las Vegas Wash, I traveled around much of the world, such as Asia and South America, photographing the ordinary and unremarkable, places unnoticed, except maybe when they are captured in a photograph.

In August of 1998, I drove down Pabco Road off Boulder Highway for the first time in twenty-six years, looking for the Las Vegas Wash and the Ponds. The Ponds was an area where the nearby industrial factories sent untreated effluent to settle out before the water seeped into the water table or was evaporated. While at times toxic, these ponds supported hundreds of migratory and resident species of birds. My count list by 1972 was 333 verified species. Led by memory more than maps, I did not find what I had once experienced. The words of Aldo Leopold, who cautioned against returning to the landscape of one’s youth, echoed often in my mind in those first days of return.

“It is the part of wisdom never to revisit a wilderness, for more golden the lily, the more certain that someone has gilded it. To return not only spoils a trip but tarnishes a memory.”

Well, Leopold wasn’t far off the mark. The Ponds no longer exist. The nearby Henderson Water Reclamation Facility has created from their sewage treatment ponds a manicured bird watching preserve, complete with interpretive signs, benches for resting, paved pathways and strategically placed trash barrels (twenty-nine at one counting) for visitors to dispose of Big Gulp cups and food wrappers while peering for American Avocets and coots.

In her passionate and personal account of the American desert, Mary Austin described this arid environment as a “land of lost rivers, with little in it to love; yet a land once visited must be come back to inevitably.” Austin’s defense of the deserts of the Southwest is a testimony of an aesthetic of harshness – her narrative is written with the observations of a naturalist and from the heart of a poet. In order to fully appreciate “the land of little rain,” she wrote that one must give the land a year, a year in which to witness the procession of climate, light, color and life. A season to experience all that a place is, all that a place represents. It was my reading of Austin that led me to define my project in the Las Vegas Wash as consisting of a year beginning in the summer of 1998. Since that initial year, I completed two other photographic projects and a short documentary about the once wild and now urbanized Las Vegas Wash. Of the places I frequented and photographed during these projects, nothing has remained the same. In some cases, these places, like those early ponds, no longer exist. One reason why my own favorite spots are gone is because of large-scale restoration projects, flood control engineering, and the creation of an urban park. To create a park from what was once a wild and difficult to access swamp, is to diminish the wild experiences such a place provides. Such restoration projects, such as the Desert Wetlands Park, weed out the wild, to paraphrase Gary Snyder.

The Las Vegas Wash should be protected as a wetland, not because it is wilderness or nature, but because it is cultural, urban and man-made. It is a landscape where we can learn about our relationships with the desert, it is an expression of a social order as well as a natural occurrence. In Las Vegas, we belong to the desert, a place we both deny and accept. Landscape theorist J.B. Jackson describes the value of ordinary places and how we should understand and appreciate them.

“This is how we should think of landscapes: not merely how they look, how they conform to an esthetic ideal, but how they satisfy elementary needs: the need for sharing some of those sensory experiences in a familiar place…”

If we are to preserve or maintain places like the Las Vegas Wash, then we must inject into our studies and understanding some sense of the transcendent. The sciences of hydrology, ornithology, botany and geology, the pursuits of economics and land use must be accompanied by and balanced with a poetic sense of appreciation that goes beyond mere description, restoration. This is because the Las Vegas Wash is more than an environment, or an accident in the desert. The Las Vegas Wash, is an environment where the residents of the Las Vegas valley can ask fundamental questions about why we are here in this desert and what are we doing to this place. We must go beyond habitat, scenery and parks. Wallace Stegner’s admonition should be taken here because,

“No place, not even a wild place is a place until it has had that human attention that at its highest reach we call poetry.”

Fred Sigman

Las Vegas, Nevada

October 2008