The East Mojave: America's Outback

Gallery

This photographic project consists of a series of black and white portraits each paired with a color landscape photograph; both photographed with a 4x5” view camera. The region and its people have been photographed with an equal interest in the natural as well as in the cultural. There were some who preferred not to be photographed, fearing again that their identities and location might be compromised. I assured them their identity was protected during a one-minute exposure. People live "off the grid" for many different reasons. For some, it is simply to maintain personal privacy; for others it is to hide from authorities or because of a general distrust of strangers (aren't we all?). And of course, many people and families live across this land as they work their ranches.

Field Notes

The Nipton community of about forty residents was not an easy one to be accepted into. Except for the owner and one other resident, my house was the only other house; everyone lived in an RV or trailer. The residents of Nipton were either retired, worked in Searchlight across the Nevada border, or at the Molycorp Mine in the mountains. When I first arrived, no one knew what I did (I was a university professor), and noticed that I only came to Nipton on weekends. Late to arrive on Friday, early to leave on Sunday, I was a shady character to them. After having the house for a month or so, I decided to introduce myself to other residents. One night, across the road in front of the old school house, a group of about five guys sat around a fire, playing guitars, and drinking beer. I strolled over with two six packs. As I approached, the music faded and I do believe the fire even started to go out. They looked up at me without a word. “Hey, I’m…” is all I could say when one of them (Jeff, who later became a good friend), said, “We know who you are. Now, take your faggy beer and head on back across the road.” They were drinking Natural Ice, I had St. Pauli Girl. I would later learn they all thought I was a narcotics agent; why else the strange behavior and comings and goings? Eventually, we all sat around that fire drinking Natural Ice, but it took a while.

Everyone in the Mojave is given a nickname, and mine was “Narc.” In spite of the distances between towns – Nipton is a twenty-five mile drive from Cima - everyone knows everyone. I drove out to Cima one morning to meet Irene, who ran the general store and was the postmaster. I had hoped she would agree to let me photograph her and to also make some photographs around her place. I found her sorting mail when I came in. “Hey, I’m…” is all I got out before she said, “I know who you are. You’re the Narc.”

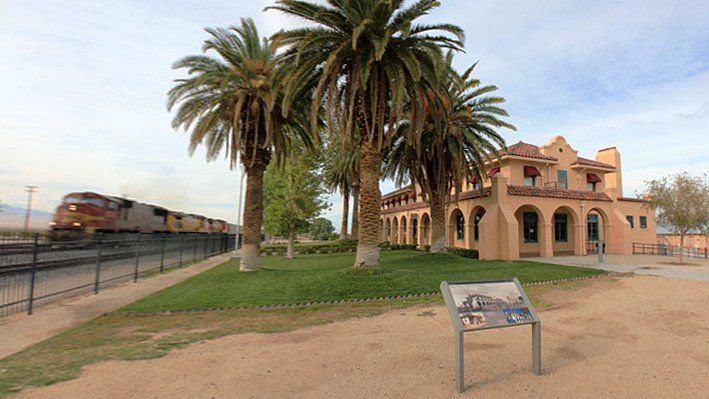

The East Mojave Preserve is bounded by highways and roads. Interstate 15 on the west, Interstate 40 on the south, with Nipton Road creating the preserves northern boundary. At its eastern edge is US Highway 95. This area of the Mojave Desert is also known as the 'Lonesome Triangle.'

Such boundaries are arbitrary in many instances; matters of convenience, really. Most of the tourists who travel on these interstates are probably unaware of the existence of this national park beyond of their windshield. Traveling in a hurry to get to California or Las Vegas, they see that emptiness and avoid its imagined tracks of nothingness.

Within the preserve’s roughly 1.4 million acres is some of the Southwest's most beautiful and diverse desert landscape. The seven-hundred-foot-high Kelso sand dunes are not far from the caves known as the Mitchell Caverns. Volcanic cinder cones face the forest-covered mountains known as the Providence and New York. What always stimulated me in my travels through the East Mojave Preserve was its valleys, both vast and expansive. With names such as Landfair, Clipper, Round, Pinto, and especially Ivanpah, these were places where I experienced the sheer joy of driving through a space which receded to a far off horizon.

My fascination for the near infinite stretches of land in this preserve has been matched by my curiosity and interest in those who have chosen this desert to be their home. Or, in some cases, much like my own, as their own personal place of refuge.

Beyond, or perhaps I should say within, this landscape is a diverse population of people, spread far apart from one another, who are neighbors in the East Mojave. Some of them have been there for generations, while others but for a short time, waiting for their next destination to be decided upon.

After three years I gave up Quail House. As of 2018, when this essay was written, Irene has been dead for about seventeen years and the community of Cima is now a ghost town. Its claim to fame for several years was that it had one of the last functioning phone booths in all of California. You can see a picture of this phone booth on my Contact page of this website. After Jerry’s death in 2016, Nipton was sold to American Green, a cannabis technology company that is creating a marijuana destination in this century-old railroad stop. Most of the residents I knew in Nipton have left. A couple were arrested. Others moved on in search of work after mine layoffs. A good friend committed suicide after his cancer returned. But most, just evaporated, as so much does in the desert.